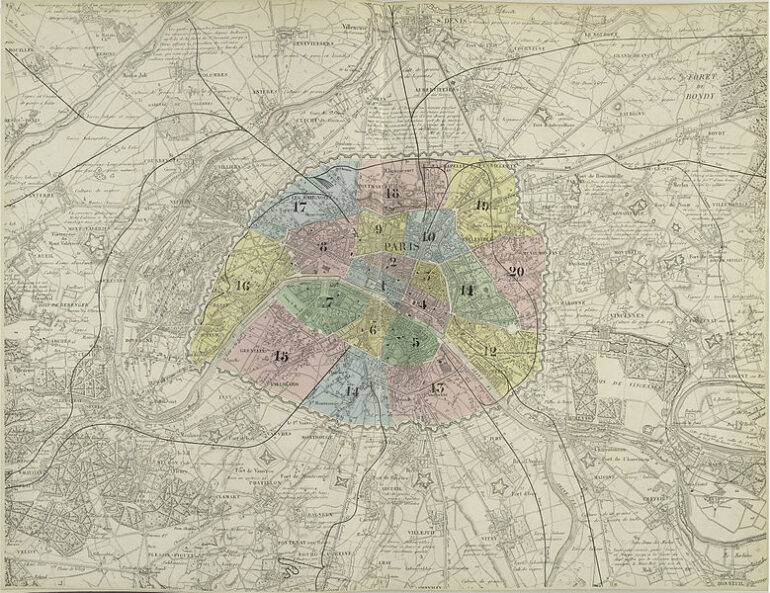

In 1795, the city directorate separated the sectors of Paris into 12 ‘arrondissements.’ The capital city stretched all the way out to the surrounding farming areas. This arrangement was then replaced at the beginning of 1841 with the birth of ‘de Thiers,’ which encompassed 24 independent communities. In 1860, Napoléon III, who dreamed of a grand Paris, decided to join them all together. The capital city, already considerably stretched out, was then regrouped into 20 arrondissements – these were all laid out according to their numbers. Following on from this separation that was adopted by the first 12 arrondissements, from west to east and north to south, there was a tricky problem to overcome – the current 16th Arrondissement changed to be named as the unlucky 13th, and this risked causing offence amongst the middle-class locals that Napoléon III was already applying political pressure on. The mayor of Passy found the solution. He devised a numbering system that was called ‘The Snail,’ where the central district of Paris to the north of the central island of the city became ‘No. 1.’ The numbering then continued in a manner that resembled the points of a watch face. In its entirety, Paris then presented the layout that we have become familiar with today – a lively centre, full of monuments and scarcely populated, a western area that is spacious and rich, and an eastern area that is open and populated. Unlike the modern-day Paris, each arrondissement had a unique personality, and when combined together they resembled a kind of ‘patchwork’ layout of metropolitan identities. Even if Paris has changed enormously since 1860, this atmosphere is still present in part.

More from Secret de Paris - Hôtel & Spa

Place de la République

This vast rectangular area dates back to the era of transformations that...

Read More